Biblical Hebrew Considered as Independent of 3-Consonant Root Structure

Introduction

The following article is conjectural, as it must be, due to a lack of resources. Its premise has been found in at least one other source, though the focus is somewhat different. The fact is that most Semitic words are based on roots of 3 consonants – something which may hold a mystical significance for some readers, but we believe that an argument can be made that this was a later development within that language group. We will present arguments for a simplified root structure, written with the general reader in mind.

The article starts with some consideration of the aforementioned root structure, criticizes some of the source material, consider the original language (perhaps pre-Semitic) as having only two phonemes, and based on the comment of one of our sources, we discuss the possibility that a two-consonant source or root, M-R, can, perhaps with more imagination than convenient, lead to over 90 3-consonant words derived from the meaning of the same root.

This, the preceding, and the following two paragraphs are new additions to the 2018 article. We felt that the introduction should have been a bit clearer. We are also critical of our unclear presentation of methodology, the ideas of which are found more in the text of the images than in the body of this article. To remedy this defect, we will here state that the fundamental idea presented by the letters M and R, when together, suggest bitterness. We then suggest, in other images, that certain groups of words, although of themselves having nothing to do with “bitter”, are derived from the same root because of, for example, something that may have resulted in a bitter feeling to others (obstinacy), or bitterness of a material (ointment, and hence the idea of anointing).

We shortly hope to have a companion page to this, which will go into a deeper analysis of another letter, with the proper explanation of the methodology folllowed, something which here is not up to the standards we expect of ourselves, and which cannot be remedied without tearing the existing article apart. It was constructed on enthusiasm with the ideas, not on a painstaking analysis.

It has been noted that some computer screens do not sufficiently show the images, which are an integral part of this article. If this should be the case, it would be necessary to download the images, and view them by other means.

The Three-Consonant Root Structure

While by no means applicable to all Semitic words, their basic structure requires 3 consonants, some of which may appear to the non-initiated as vowels. However, it is unusual to include these, except for very special purposes.

The vowels may be placed in front, between, or behind the consonants. That may seem obvious, but regrettably, it is only apparent. When the parent to our letter “A” begins a word in Arabic, it is not a vowel, but a consonant, so the statement at the beginning of this paragraph is incorrect. Nevertheless, for the purposes of analysis, we might count this letter as an honorary vowel, should we try to calculate the number of roots that could be formed from any root.

Of special difficulty in counting the number of words which could be derived from a given number of consonants is the consideration of possible consonants which can elide without a vowel. In English, for example, we can have bl, br, ch, chl, chr, cl, cr, fl, fr, and others, but not dl, yet dr is permitted. Therefore, to know the exact number of possible simple words that could be derived, we must not use pure mathematics, but an analysis of the structure of the language.

This explains, in part, why Spanish and Italian, as a rule, must end words in a vowel (excepting the letters, in Spanish, d, l, r, s, and z). Japanese has its own rules, the only final consonant is n, and vowels must be inserted between all consonants, which is why the word “croak” in English becomes “ka-ra-o-a-ke”.

Because of a criticism that will be made of one of our sources, we will use the Arabic as an example to start with, with their alif, waaw, and yaah. – which we will transcribe with the English letters A, W, Y. The vowel equivalents would be A, O or U, I or Y. However, we count these as 3 vowels, not 5, because we are not interested in the sound that they have in a given word.

Let C be any consonant.

C-C-C is an unvowelled root, as such, cannot be pronounced. A usual root structure begins with the “a” sound following the consonants. Any non-initial consonant may geminate, that is, double, thus we have additional possibilities, C-CC-C, C-C-CC, and what we have never seen, but arguable C-CC-CC, which we will ignore. If, in the following table, we see CC without a following vowel, it must be considered as a non-geminated form, because otherwise, the root would only have 2 consonants. There exists a special ending for the form of the words not prefixed with the equivalent of the English “the”, with which we need not concern ourselves.

The resulting possible words (never in fact) would be more possibilities than we can safely admit to – many will be practically, in not theoretically impossible. Our math has given us 1,436,400 words – more than in the English language.

Such a marvellous potential vocabulary is far beyond the necessity of any of the ancient peoples, and even of our contemporaries. Maybe a multilingual person can manage that many, but in most cases, they would be word forms which look the same, but with different meanings in different languages, such as the German word for day, which looks like the English word “tag”. Thus, by giving words the possibility of more than one meaning, we multiply potential meanings to the level of that useful to a civilization superior to our own.

We have not even gone into the subject of Semitic infixes, suffixes, and prefixes – we believe that our point has been made.

Roots of Two Phonemes

Because the richness of the vocabulary of a language which could be generated as described in the previous paragraph goes so far beyond what is required of non-industrial, or even pre-civilized societies, we believe that it is more convenient to look for a root simpler than that described above. Certainly, the Proto-European language has such roots, occasionally with a C-v-C form, where “v” is a vowel, but usually, v-C, or C-v, where the C could be equivalent to a strongly aspirated consonant, that is, one with the puff of air of the letter “h”. Occasionally, an initial consonant is followed by “r”, or “l”, but this is more usually in words later derived from Greek or Latin. However, we think this idea deserves some consideration even in the Semitic languages. In the present article, we have specifically chosen Hebrew, as our sources do not emphasize the triple-consonant structure as much as do those which we have for Arabic.

A Preliminary Critique of Our Source Material

Now, to the best of this writer’s knowledge, this article was started on December 29, 2017, and was to be linked with an article started December 27, but not yet on line at the time of this writing. This is important, because we found that one of our Hebrew dictionaries was Part I, while our research required Part II: It was then that we found a book on line, on January 2, 2018, which purported to show ancient Hebrew Roots. This timeline is important, because we found that the book in question somewhat deals with the same ideas that we do here.

In some ways, the author of that book must be a kindred spirit of the present writer, not only for the shared idea, but for the number of spelling errors. We sincerely hope to have done better, but our senses are weakening.

That meanings of 2 or 3 letter roots may appear to be the same, is based merely upon observation, and our pre-existing knowledge about Arabic and Hebrew. By emphasizing the English of the Hebrew words, anyone can easily evaluate the validity of the present argument. Our charts even admit to some of the false etymologies: some of the true etymologies have been underlined in red.

We criticize the work for the following reasons (without having gone too deeply into it, to prevent contaminating our own line of thought):

- Page 41 of Jeff A. Benner’s Ancient Hebrew Lexicon of the Bible, under the title “Letter Evolution” spells “tounge” for “tongue”, “fractive” for “fricative”, and “puss” for “pus”. We were asking ourselves at “fractive” if this was some kind of alternative word, and by the time we found the third mistake, we were nonplussed, and wondered what made the author of that work think that a puss was yellow.

- His idea which approximates ours is that of parent roots. He had chosen the Hebrew word for yellow, below, our random choice was for the word bia. We appreciate his idea of listing 529 of these two-letter roots (p. 45). Unfortunately, the concept of parent and child roots, when a web search was done, always referred to that author, which may be the fault of the search engine, but suggests that his idea is expressed (as is ours) in an original form, to which a new name was given. We give no such name, and remain purely descriptive.

- On page 35, Table 7, a number of words are given which supposedly have a common root meaning “break”. Below, we have done a similar, but deeper, analysis with words related to “bitter”. Again, we have a difference in style: Benner is dogmatic, making the words fit, by creating definitions which may indeed be correct, but were the reader to look in a Hebrew dictionary, his definitions may vary. This author would be more confident if Benner had allowed the reader to come to his or her own conclusion as to the common root of these words. This is what we do below. The reader is allowed to reject or accept our thinking, and we acknowledge some false reasoning which we used. In this sense, this work will serve as a warning to others not to take their own conclusions too seriously without prior consideration of their reasonability.

- The ‘ayn (to give an approximate English rendition, is considered to be a vowel. This writer rejects that idea, at least for purposes of simplification. Described as a guttural, it would be a consonant. Benner gives the same pronunciation to ‘ayn (written there as ayin”) to ‘ayn + bet as to aleph + bet, in effect, ignoring the guttural sound, and giving us pure English.

- The explanation of his parent and child roots is confusing, though partially correct. The derivations, he claims that there are 13 child roots, including the one which is the doubling of one of the two-consonant roots. In our example further above, where we presuppose a 3-consonant root, we get 12 basic possibilities, without any doubling. He then adds twelve more, but the explanation is confusing (p. 34-5), and includes our criticized ‘ayin in the discussion. At any rate, we do not refer to child roots in our own discussion (father above), but show that the number of derivations from any 3-consonant root is much higher, even without considering what we call infixes, prefixes, and suffixes (made with an extremely limited number of consonants), these latter giving learners complicated verb tables. Granted, Benner’s topic is the Hebrew root system, but at least in our own example, we could find no “child” roots of our M-R- root beginning with a vowel, with one or two possible Though not a statistically significant result at present, we do believe that our major premise is at least close to being so.

- Finally, the Hebrew that is used in Benner’s dictionary is what is called Ancient Hebrew, so any reader who would like to check for accuracy is first forced to learn the ancient Hebrew alphabet of the book. Our own work is transparent, and does not require knowledge which was not even had by the most serious scholars who compiled the learned dictionaries of the 19th Century.

In favor of Mr. Benner we might say that he has made a contribution to supposedly updating the etymological dictionaries of such worthies as Wilhelm Gesenius, whose work was translated from German into English by more than one scholar. There we find doubts that Dr. Gesenius or his translators had, clearly defined. Our charts below are, then, based on Gesenius as translated by Christopher Leo (Cambridge, 1825) and Edward Robinson (Boston, 1871). The works may be old, but whatever errors they may have would not be statistically significant in relation to the argument we present.

We also appreciate the fact, which we had read previously elsewhere, that because of the Semitic way of thinking, very dissimilar words might have a common root – because the tangible characteristics of a word define which other words share its sound when vocalized. Apparently, these should not be considered as homonyms.

Reasoning for Simplified Roots

We do, however, believe that the concept evolved later. One of the arguments we have is that of a certain Peyman Mikaili of the Iranian Academy of Sciences who had a plan to write an etymological dictionary of the Arabic language (what we have found in 2021 is here. He argued (in a webpage no longer available) that the Hebrew language is much poorer than the Arabic, the latter, he claims, has more than 10,000 root words, while the former has 4,000 to 5,000. [The present writer would argue that there must be much less in the proto-Semitic language.] There are language specialists who would disdain the argument that any language is less rich than another, but let us for a moment suppose that there were an element of truth in his contention. If, in a faith-oriented world, admittedly one that is becoming smaller and smaller, the first language must be Hebrew, it would follow a principle that mathematicians call elegance – one of the components of which is simplicity itself. An example of this is the formula for the speed of light by Albert Einstein – something very complex is expressed in at most 5 terms, e=mc2.

For the foregoing reason as a hypothesis, we repeat our suggestion that the original language had only two phonemes – a vowel and a consonant – we do not care which order, nor do we exclude one-vowel words; or perhaps, an easily-pronounceable two-letter consonant beginning (quite dubious) plus vowel (diphthongs being counted as such for the present purposes). This would bring us in line with Chinese radicals, and many of what this author considers to be an excess number of Indo-European roots. Why should these exceed the number of Chinese radicals? This author has no intention of disdaining European culture, but the common graduate of a few years of education might have learnt that Mesopotamia was the cradle of civilization – we do not ignore the theory that our ancestors may have come out of Africa, but we are interested in written records, not bones, tools and pottery – and it is mostly ignored that China rivalled the Roman Empire in size 2000 years ago.

Let us consider, before going to the Hebrew, some Chinese words: Mao, Tse, Chou, Lai, Chi, Tai, Pei. If the old Mao Tse-Tung is now written Mao Zedong, by convention, the fact that Tse and Tung were separate elements has become hidden. Spaces waste paper.

What about the “ng” ending of “Tung” or “Zedong”. This is a nasal termination. Since we are referring to Chinese, we need not bother any more with this, accept to note that many Indo-European roots allowed nasal infixes – these followed the development of the root. This does not mean that we are claiming this for any other language, without closer examination.

We might also consider place names of South-East Asia: My Lai, Ha Tinh, Khanh Ah (from Vietnam, names may have changed since 1961) and Chau Do and Phnom Penh in Cambodia. (The “h” may be ignored as much as the “n”, at least for the Western reader.)

Reconstruction of Hypothetical Roots of Hebrew

In this section, we make an argument which should only be considered on the basis of the evidence provided in our charts (below). The reader might also take Jeff Benner’s word for it, on the basis of much less evidence.

Let us take our double phoneme, v-C, or C-v [v(owel), C(onsonant)]. We get, for example, in Hebrew, “El”, as in the name of the airline, El-Al, or the portion of names such as Samuel, Rachel, and Michael, where it means “G-d”, the Deity.

We get words that are written as one letter in Hebrew, as in Arabic, but as sounds, conforming to the C-v construction. These are usually preposition or conjunctions at the beginning of words, the Hebrew “B”, as, for example, in or at, a form of “h” (5th letter) meaning “the”, the 6th letter, vav, meaning “and”, the equivalent of “L”, written alone, similar to “B”, or with an aleph, meaning “no”, words like “nah” with 3 meanings in one source, one being “now” in the sense of “oh” (naw!). We should consider some words beginning with the “vowels”, ab, father; ad, mist; av, or; az, then, since, etc. Now, moving on to the letter vav, only 10 entries are found in one work (Langenscheidt), one being the letter itself, the second entry mentioned above [the word “and”, plus other “conjunctions”], and a third being the name of the letter, that being “vav”, “v-v”, nail or hook. Robinson’s translation of Gesenius gives 15 translations over 5.3 pages, about 3 of these dealing with the letter itself, – vav is given an unknown origin. [Benner would have it that it was the Semitic pictograph of “peg” – a translation of vav, as its etymology, making the origin of the pronunciation irrelevant, if we understand correctly – because it is the ancient Semitic writing which is what is important. (In the “yod” “vav” “yod” word, both the “vav” and the “yod” should really be considered as functioning as consonants.)

As a possible interesting aside, this author attempted to make some clothes pegs some years back from some branches of a magnolia tree, one of these, if viewed at the correct angle, does look like the Hebrew letter under discussion.

But the preceding, except for the last two examples, are one-consonant constructions, properly considered, as it is the reader who must supply the vowel.

So let us go on to consonant constructions, where we agree with Benner to see roots of three-consonant words. Our charts elaborate upon this, by giving both genuine and apparent evidence. What is not real is included to warn others interested in etymology, as stated before, to be careful in coming to any conclusions.

For a teaser, let us present the word Babylon, or Babylonia – root BWB in Arabic, but irregular, and coming out to baab. The second component is El, which according to one’s religious beliefs (if any) is the common root for Hebrew Elohim or Arabic Allah.

Bab-el, then, was the Gate of God, or the Door of God, anything after the final “B” was a suffix.

We compare this to the Biblical Hebrew word meaning entrance; bia, or “to go in”, bo, (beth, waw, aleph). Some might argue that the Hebrew was derived from the same language as the Arabic, and that may be true, but for the present, the important point is that the Hebrew presents us with something closer to the sought-after 2-letter combination. [Properly speaking, some constructions are defective, like the English verb pattern for “must”.] “To go in” is in effect a consonant plus vowel combination, with the second vowel affecting the pronunciation, if at all. Even the word for entrance, if mispronounced, would be a consonant plus diphthong.

The derivatives, if any, from what may be a “Hebrew” “two-letter” root are too daunting for this writer to undertake, without stretching the credulity of the reader, so we will go after a word which will be obscure to the majority of readers, but make our argument more clear.

Let us work with the Hebrew root M-R, which our dictionary (Langenscheidt Pocket Hebrew, Karl Feyerabend) presents as two different words, though admitting of a third. The first of these is mar, meaning a drop, by which we might suppose that the Spanish for sea, mar, or the French mer, is the mother of all drops. The second word, pronounced the same, is an adjective or noun, meaning bitter, sad, embittered, fierce, violent, bitterness, and sadness. Some writers have said that this, in the meaning of bitter, is the origin of the word Mary. A sad conclusion – why could it not be our third possibility, pronounced “mare”, meaning myrrh, even if Wikipedia does connect that substance with the root meaning bitter?

Benner (this is a paragraph added after our original version of this post) derives M-R from the ancient Hebrew script, the “M” being represent by a symbol for water, and the “R” by a head, from which the Hebrew letter is named “resh” or “rosh”, meaning “head”. It is argued that this symbolic representation of myrrh means head-waters, which often collect in stagnant pools, such as in a marsh. In this author’s secondary school science class, a marsh was a place where entropy sets in, while head-waters flow, flowing waters are not bitter, but sweet. This author has drunk from a thermal spring, and from a river flowing from the mountains, and the waters were sweet! The marshy areas he knew were near the mouths of creeks with often dried.-up headwaters, so it is felt that the argument in Ancient Hebrew was forced. Not to discredit it completely, it is suggested that the headwaters could be from a salty source, or from one contaminated with what 3000 years ago was practically surface-level petroleum in the Middle-East.

So now, we present our own argument in support of our thinking.

What derivatives can we get from the above? Firstly, we would prefer to see our 3 roots unified. The drop is a tear-drop of sadness; myrrh is a drop of resin, according to the Webster Collegiate Dictionary, with a slightly bitter taste. Note, that by using the just-cited definition, the words drop and bitter could all be integrated into the second meaning. While this is not proof of itself, it may bear consideration.

After a careful reworking from an original count of 92 words, including the 3 mentioned above, beginning with M-R, we find, in the reference used, 111 words (a prior count gave 114), of which we were able to fit all but 6 into a common meaning. Omitted were the series A-M-R, I-M-R, which would make an additional 12 words, 8 of these beginning with Aleph, all of this group seeming to be of a completely different root. (One or two of the I-M-R series could be fitted in, but was not.) Thus, our randomly selected word allowed us to conclude, without any sophisticated knowledge of Hebrew, to deduce potential relationships between 75, 86, or 93 per cent of all the words, depending on whether we include those beginning with Aleph and Yod, exclude the former of these as irrelevant, or exclude both of these.

The charts ignore redundancies which our source may have provided. [Please see note at end of article.]

If we look at the entries of page 1 of our table, [or see pages 194 to 198 here] in the first dark insert beside the red page number, we see the 3 entries to which we have referred. Wikipedia, spurned as a source by many universities, would seem to justify our inclusion of the word myrrh with the meaning of bitter, and gives a Semitic root M-R-R. That such a root exists for “bitter” is confirmed in our Sopena Alhambra dictionary by Maurice Kaplanian (Arabic-Spanish – Spanish-Arabic), but the chief meanings are quite distinct there: to pass – in time or place, or to go through, with many of the meanings being about traffic. That root would not allow itself to be reduced to two, as we have done here with the Hebrew. The meaning was confirmed with the more complete Arabic-Spanish Dictionary by F. Corriente.

Click on images to enlarge.

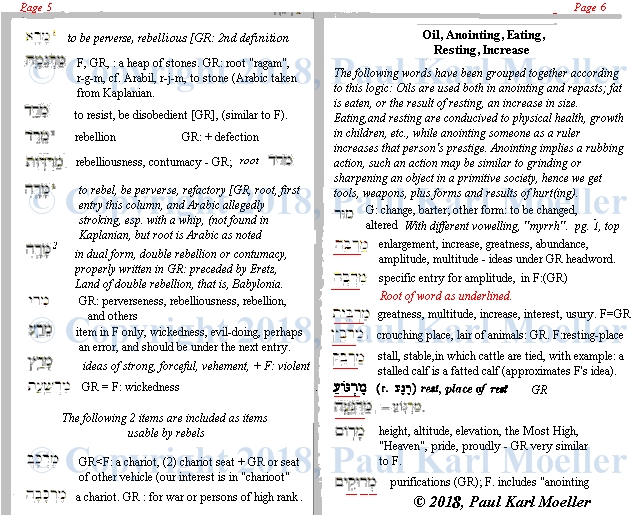

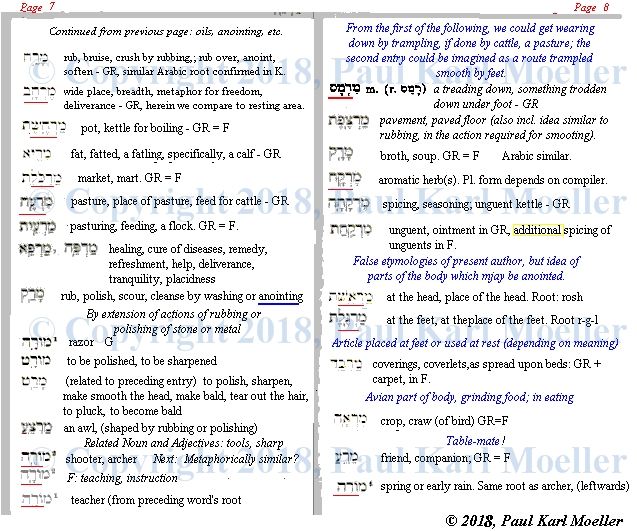

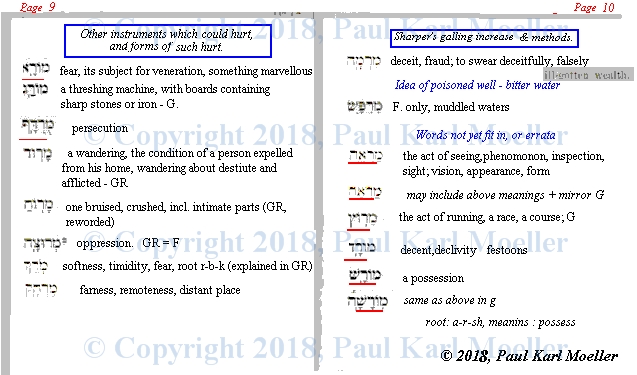

Table 1 – Roots of Biblical Hebrew Word for myrrh.

“F” is Feyerabend, R is W. L. Roy, https://books.google.com./books?id=qF1gAAAAcAAJ&dq

Here is the second table, where, in addition to the abbreviations “F” and “R” given above, we have “G” for A Hebrew Lexicon to the Books of the Old Testament, Part II, Wilhelm Gesenius, trans. Christopher Leo, and “GR” for A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament, 20th Ed., William Gesenius, trans. Edward Robinson. The original idea was to compare the translations, but later, the use of the two was to expedite the search of words in our slow computer, by searching those words with an alpha or yod in one dictionary, and the ones beginning with mem followed by rosh in the other.

Our charts, created on the fly, had the words of the supposed common root listed in various groups. These may be described as follows, (data is to be revised – the original charts were different, and we need to give a new break-down, including the correct number of words which could not fit in with the primary idea.):

Nine words were related to the idea of bitterness, sadness, or the like, plus we must include the first 3 in the list, giving 12. This excluded 5 proper nouns – one being a well with bitter water, and 3 of them having to do with Babylon, in one way or another.

There are an additional 5 place names, and 12 more names given to people, including Mary or Miriam, which some authors say has the word bitter as its etymology. Strictly speaking, the remaining cannot be said by this author to be associated with our common root, but we are suggesting that this is so.

Bitter to a parent would be obstinate or rebellious offspring. From this idea of obstinacy, we get an additional 15 words, including the idea of hurting. Because we included war-chariot (as a potential instrument of rebellion), we could perhaps have included another word “chariot”, which was left orphaned, and perhaps even “race”, in the meaning of a type of competition (and it occurs to us that the winner may be “anointed” – a meaning given next.

The idea of myrrh, being a substance used in anointment, gives the possible branch of meanings of oil, fat (used in anointing or in eating), eating may be associated with a time of resting, an anointed person increases his prestige, the person eating increases weight, and the person resting increases his health, hence, we include the idea of increase. This gave us 48 words, which we analyze on pages 4 and 5 of our table. Through anointing, for example, we get the idea of rubbing, which might imply polishing, or the shaping of tools or weapons – the latter causing hurt. It has been maintained that the Hebrew idea of synonyms is not about what looks the same, but what shares the same properties, so (the exact example escapes us at the moment), a fast bird may have the same root as a fast mammal.

We note that what we show above does not correspond to what one finds in dictionaries of the Arabic language. An idea of a possible root is certainly useful, but the fact is, (v)M(v)(R)(v)(any other consonant) versions of the supposed root MRR, where (v) is any optional vowel, mock the required Arabic structure, (v)M(v)R(v)R(v), where infixes, prefixes, and suffixes are ignored. Arabic irregularities are the result of certain vowels, not the consequence of substituting one consonant for another.

A cursory glance at words under another letter present similar opportunities; for example, we could repeat the above phenomenon with Biblical Hebrew words of the form (when anglicized) P-R-). (But now, writing 3 years later, we do this not for a double-consonant root, but for just the letter “Pe”. Whether P-R- contribute a more robust block of words will be a separate question in that article.)

We offered the preliminary version of our work to the public on this last day of the year 2017, and added tables on the second and third days of the following year.

December 31, 2017, January 5, 2018. Improved introduction: April 9, 2021.

© 2017, 2018, 2021, Paul Karl Moeller

Note: The Feyerabend dictionary was using as a point of departure, on the assumption that it was not copyrighted, as presumed in archive.org. This is a question for debate, so copyright-free translations of Gesenius were used, and Feyerabend only mentioned in the rare instance that he had provided a more suitable translation. Under any circumstances, the vocabulary of the Bible is not material for copyright. This author is of the opinion, that had he used a German version of Gesenius, and given as many translations as possible of each word, they would have matched those of Feyerabend. In many cases, this was already evident in the translations made by others.

Bibliography

Benner, Jeff A. The Ancient Hebrew Lexicon of the Bible Virtualbookworm.com Publishing Inc., P.O. Box 9949, College

Station, TX 77842 Accessed January 1, 2018. [Free copy no longer available.]

Corriente, F. Diccionario Arabe – Español, 3a Ed. [Herder, Barcelona: 1991].

Feyerabend, Karl. Langenscheidt Pocket Hebrew Dictionary to the Old Testament Hebrew English, 15th ed., Langenscheidt KG Berlin n.d (hard copy) and older on line copies.

Genesius, Wilhelm, trans. Robinson, Edward, A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament …, 20th Ed. (Boston: Crocker and Brewster,1871) & Google Books.

Genesius, William, trans. Lee, Christopher, A Hebrew Lexicon to the Books of the Old Testament, Part II, (Cambridge, University Press, 1828.)

Roy, W. I. A Complete Hebrew and English Critical and Pronouncing Dictionary. New York: Trow, 1846.

—– (no name), “ANCIENT HEBREW ARTICLES”, “angelfire.com/ny4/decipherment/ahpath.htm”

—– (no name), “Ancient Hebrew Derivational Morphology”, “angelfire.com/ny4/decipherment/compound.htm”

—– (no name), “METHODS OF DECIPHERMENT”, “angelfire.com/ny4/decipherment/decphm.htm”

The above 3 sites were accessed April 9, 2021, presumably one of these having been found earlier in the year.

You must be logged in to post a comment.